(page 31 in Moving to Higher Ground, © John Englander, 2021)

Antarctica and Greenland hold 98 percent of land ice. Combined, there is enough water locked in these ice sheets to raise global sea levels by 200 feet (60 meters) if it all melts. As this book goes to press, there are ominous signs of melting and destabilization in both polar areas.

Antarctica holds seven times more ice than Greenland, and therefore has that much more potential to contribute to SLR. Though it holds more ice than Greenland, it currently lags behind in terms of melt rate.

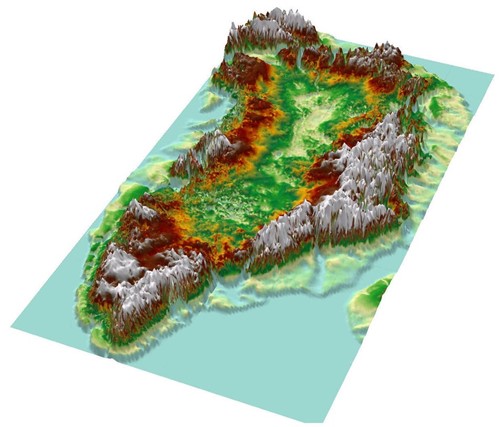

A topographic map of Greenland beneath the ice sheet from bedrock elevation data. ( J. Bamber, University of Bristol).

One factor contributing to the speed of Greenland’s melting is its topography. As you can see in Figure 3 without the ice sheet, much of its interior and outer coasts are below sea level, so the warm water is able to reach the glaciers from the surface and below. Greenland is losing ice mass seven times faster than it was three decades ago.[1] It went from losing 33 billion tons of ice a year in the 1990s to 254 billion tons in 2020, essentially doubling the amount of ice lost each decade. In August 2019, extreme heat waves in the Arctic that lasted for weeks, caused severe melting of the Greenland ice sheet. In one day, it was measured to lose 12 billion tons of ice, a new record.

Just since the year 2000, the rate at which the enormous Greenland glacier known by three different names – Kangia, Ilulissat, or Jakobshavn (“YOCK-obs-hav-en”) – moves towards the sea has tripled.[2] James Balog’s 2012 documentary, “Chasing Ice,” captures this vividly. A four-minute trailer and the full movie are available at https://chasingice.com/. They show an amazing calving event that they managed to film. Similar events has happened at least twice since.

First complete map of the speed and direction of ice flow in Antarctica. (NASA).

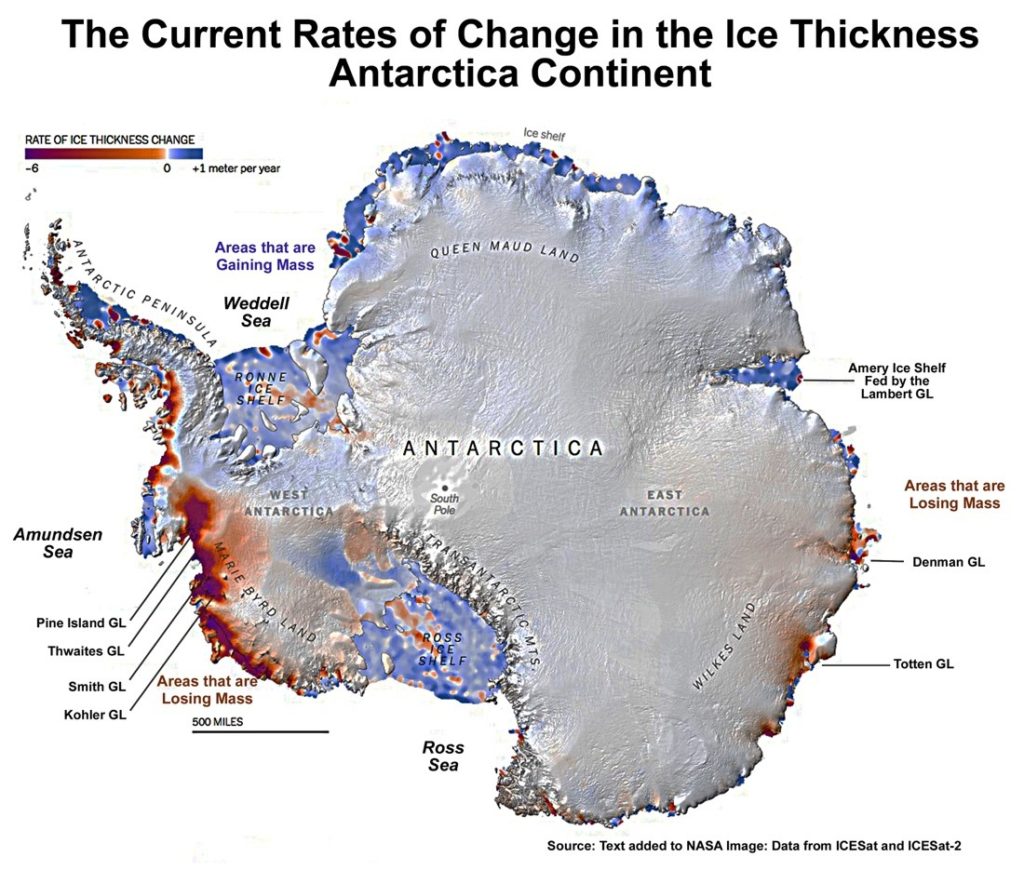

Antarctica’s mega-glaciers, Thwaites, Totten, Denman and Pine Island, will soon have better public recognition as they show increasing signs of collapse. Melt rate has increased 530 percent in Antarctica in just three decades. Ice shelves are calving icebergs up to 100 miles in length. There are troubling signs from all quadrants of the frozen continent.

Different parts of Antarctica have vastly different potential to affect SLR. The easiest way to grasp Antarctica is to break it down into four parts: West Antarctica, East Antarctica, the peninsula, and the ice shelves surrounding these three areas.

West Antarctica, the peninsula, and the ice shelves are melting at increasing rates. Because they are floating, the ice shelves in the Antarctic peninsula do not directly contribute much to SLR. But this ice shelf supports land glaciers behind it, which do contribute directly to SLR. If Larsen C melts, the melting of those glaciers would almost certainly speed up. After the collapse of the neighboring Larsen B ice shelf in 2002, researchers observed melting ice from nearby glaciers flowing as much as eight times faster.[3]

The same holds true for the other major ice shelves in Antarctica. If the Ross ice shelf, which is the largest ice shelf in the world, were to completely collapse, it would potentially allow the land ice behind it to flow more quickly into the ocean, eventually raising sea levels by as much as 38 feet (11.5 meters). Up until about five years ago, the Ross Ice Shelf was thought to be relatively stable, but now scientists are seeing signs that warm surface waters are eroding it at the edges.

West Antarctica has the potential to raise sea levels by at least 10 feet (3 meters) and has been showing signs of collapse for years. Like Greenland, much of the rock floor underneath the glaciers lies far below sea level. This allows ocean water to get underneath and melt the ice from below.

The Thwaites Glacier is one of the largest sources of potential ice loss in Antarctica. It is one of six massive glaciers often grouped and identified as the Pine Island glaciers. They comprise about 4 percent of global ice that could melt. If Thwaites fully melts or slithers into the sea, it will raise global sea level more than 1.5 feet (~50 cm). Warm water at the grounding line is melting Thwaites from below so that recently, an enormous, thousand-foot-high cavern has been discovered inside the glacier, highlighting the rapid melting and destabilization in that region of Antarctica.

Thwaites is now moving into the sea at a speed of 2 miles per year (3 km) – very fast for a glacier – and the rate is accelerating. As this book is being finalized in the winter of 2019/2020 an increasing series of earthquakes in the West Antarctic glaciers are occurring, what I call “icequakes.”[4] These occurrences add to concerns about possible collapse of those glaciers covered here. Based on the latest findings, glacioliogist believe Thwaites will soon reach an irreversible “tipping point ” though it would likely take decades, possibly a century, for it to fully slide into the sea. While that gives us some time to adapt, we must act quickly. Even when only a quarter of this glacier slides into the ocean, sea levels will rise 4 to 5 inches, globally, and will be very disruptive for many low-lying regions.

East Antarctica is the real wildcard. Although once believed to be stable and much more impervious to climate change, it, too, is starting to show worrisome signs of melting. The Totten Glacier is the largest glacier in East Antarctica. Along with the neighboring Moscow University glaciers, they hold enough ice to raise sea levels over 16 feet (5 meters). That is more than the melting of all of West Antarctica.

Between 2002 and 2016, the Totten and Moscow University glaciers lost 18.5 billion tons of ice.[5] That’s about a third of what the West Antarctic glaciers are losing each year. While most of the rock floor below the East Antarctic ice sheet is above sea level, helping to slow its melt, part of the ground Totten sits on is below sea level, just like much of the West Antarctic ice sheet. So, it seems to be vulnerable to melting in the same way as the West Antarctic ice sheet.

The Denman Glacier in East Antarctica has the potential to raise sea levels by nearly 5 feet (1.5 meters).[6] The glacier sits on a deep ocean canyon, exposing it to warming waters and making it the most vulnerable spot in East Antarctica. In the past 20 years, the glacier’s grounding line has moved 3 miles inland,indicating the potential for ice sheet collapse in East Antarctica.

[1] Mass balance of the Greenland Ice Sheet from 1992 to 2018.

Shepherd, A., Ivins, E., Rignot, E. et al. Nature 579, 233–239 (2020);

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1855-2

[2] Ian Joughin et al., “Brief Communication: Further summer speedup of Jakobshavn Isbræ,” The Cryosphere, no. 8 (February 3, 2014): 209-214, doi:10.5194/tc-8-209-2014.

[3] Glaciers surge when ice shelf breaks apart.

Dunbar, Brian. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, September 24, 2004.

https://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/news/topstory/2004/0913larsen.html

[4] “Glacial Earthquakes” Spotted for the First Time on Thwaites.

Kornei, Katherine. Eos, February 17, 2020;

https://eos.org/articles/glacial-earthquakes-spotted-for-the-first-time-on-thwaites#.XlGIEl95vwE.twitter

[5] We Know West Antarctica Is Melting. Is the East In Danger, Too?

Borunda, Alejandra. National Geographic, August 9, 2018;

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2018/08/east-antarctic-ice-sheet-melting/

[6] Scientists just discovered a massive new vulnerability in the Antarctic ice sheet.

Mooney, Chris. The Washington Post, March 23, 2020;

https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2020/03/23/denman-glacier-climate-change/